The G20 Common Framework: Whatever Happened There?

Can the Common Framework evolve from a crisis-response tool into a sustainable mechanism for expanding finance in Sub-Saharan Africa and other developing countries?

[1] Eligibility was open to all IDA countries (see list here: https://ida.worldbank.org/en/about/borrowing-countries) and countries defined as least developed by the United Nations that are current under any debt service to the IMF and World Bank.

Summary: With the United States having assumed the Presidency of the G20, what can we expect from the Common Framework (CF) debt treatment process and the G20’s larger debt sustainability agenda? This note reviews the first iteration of the CF; looks at efforts to improve the CF process; and considers whether the G20’s efforts are likely to improve debt sustainability for lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs), an issue especially relevant to Sub-Saharan African countries, which face higher sovereign risk premiums than other emerging markets.

It is likely the CF can be turned into an improved restructuring process, with a clearer path for debtor countries and better coordination among creditors. However, the extension of the CF to countries with liquidity issues but not at imminent risk of default is unlikely. Moreover, debt vulnerabilities among LMICs stem from structural factors that will not be overcome in the short term.

The note also considers what steps the G20 can take to improve market access and lower sovereign credits risk. Key takeaways are:

A clear CF architecture, with early involvement and better communication with private sector creditors, is key to lower resolution and recovery risks.

To be effective, G20 efforts must directly address the structural factors that drive sovereign credit risk.

Efforts to increase the lending space of Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) should be paired with lending targeted to directly support liquidity and debt sustainability.

1. What is the G20 Common Framework?

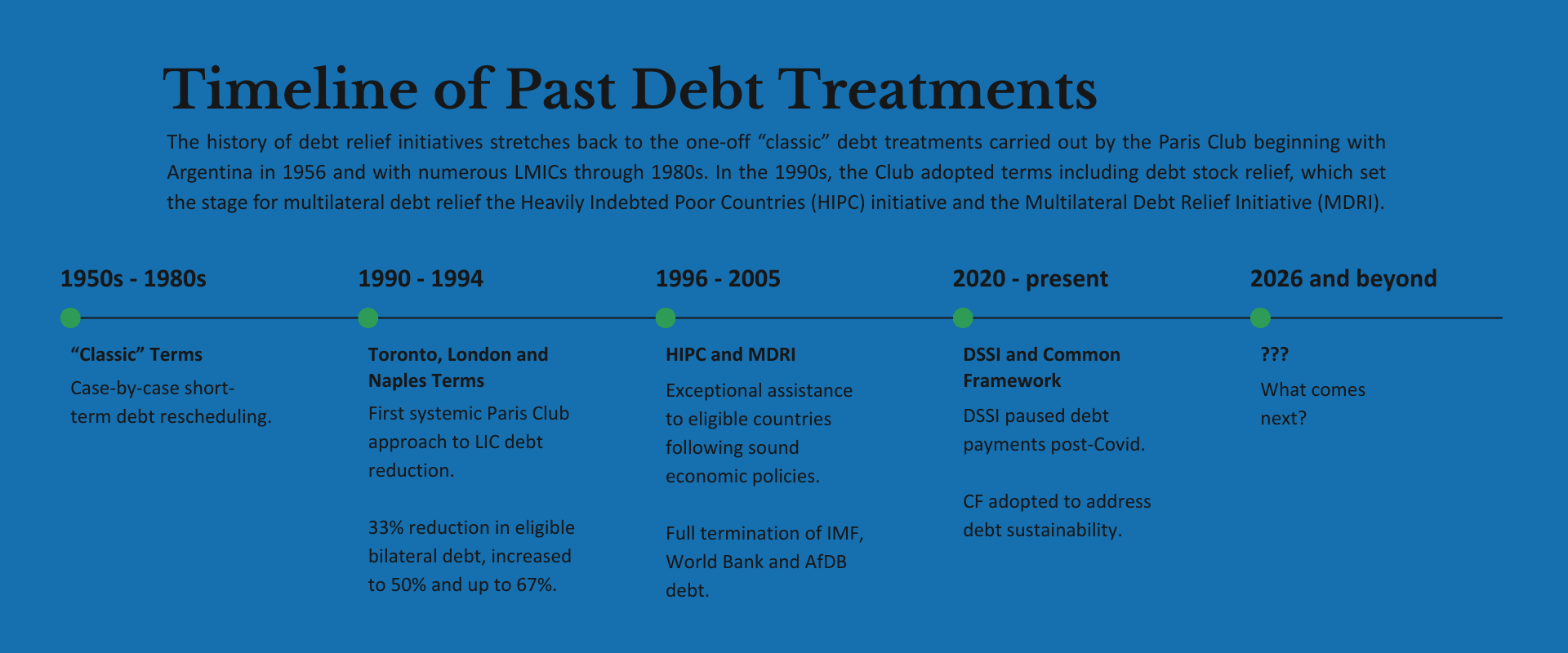

In 2020, the G20 and Paris Club jointly launched the Common Framework for Debt Treatments as the successor to the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) for Poorest Countries. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, official bilateral creditors suspended principal and interest payments through 2021 for 48 of 73 eligible countries under the DSSI. [1] The Common Framework was subsequently adopted to address ongoing debt vulnerabilities not met by the DSSI.

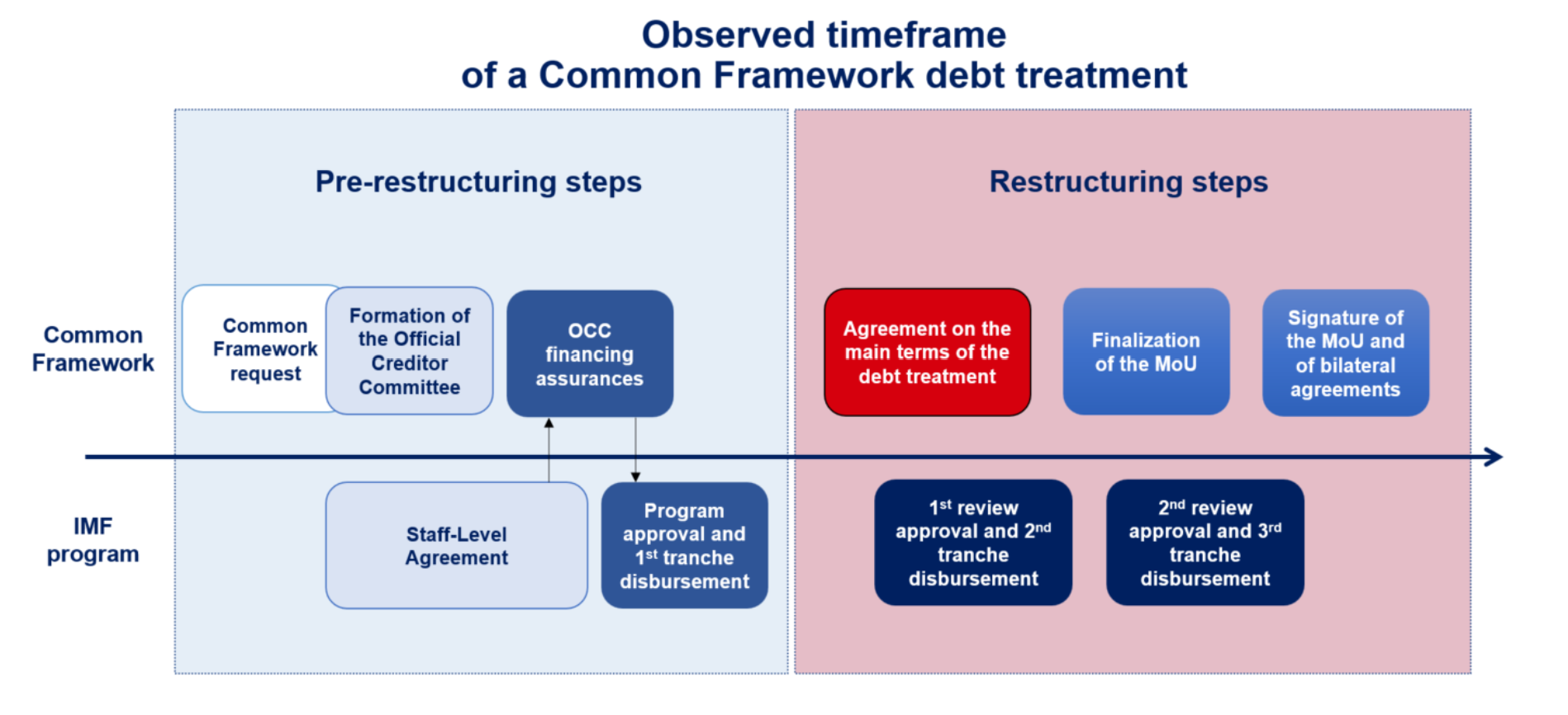

Figure 1. The CF process can be viewed as two sets of concurrent processes, one with creditors and one with the IMF, each split into “pre-restructuring” and “restructuring” steps. Source: https://clubdeparis.org/en/common-framework

The Common Framework’s core features are a case-by-case debt treatment, guided by an IMF-World Bank Debt Sustainability Analysis, and with full participation and comparability of treatment among creditors (see Figure 1 for the observed timeframe). The process is initiated by a request from the debtor country, which begins discussions with the IMF on a macro framework that restores debt sustainability and ensures balance of payments financing. The request also triggers the formation of an Official Creditor Committee (OCC) of bilateral debt holders tasked with coordinating discussions with the debtor country and agreeing to “financing assurances” consistent with restoring debt sustainability.

The IMF program is meant to fill the debtor country’s financing gaps while the OCC and debtor country government come to agreement on the parameters of a debt treatment. The parameters of the treatment are recorded in a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU), which then serves as the basis for debtor countries’ negotiations with private creditors. Importantly, the MoU requires debtors to seek terms from other bilateral and private creditors no less favorable to the debtor than the terms agreed with the OCC.

Figure 2. The DSSI and Common Framework exist within a larger history of debt relief initiatives and debt treatments.

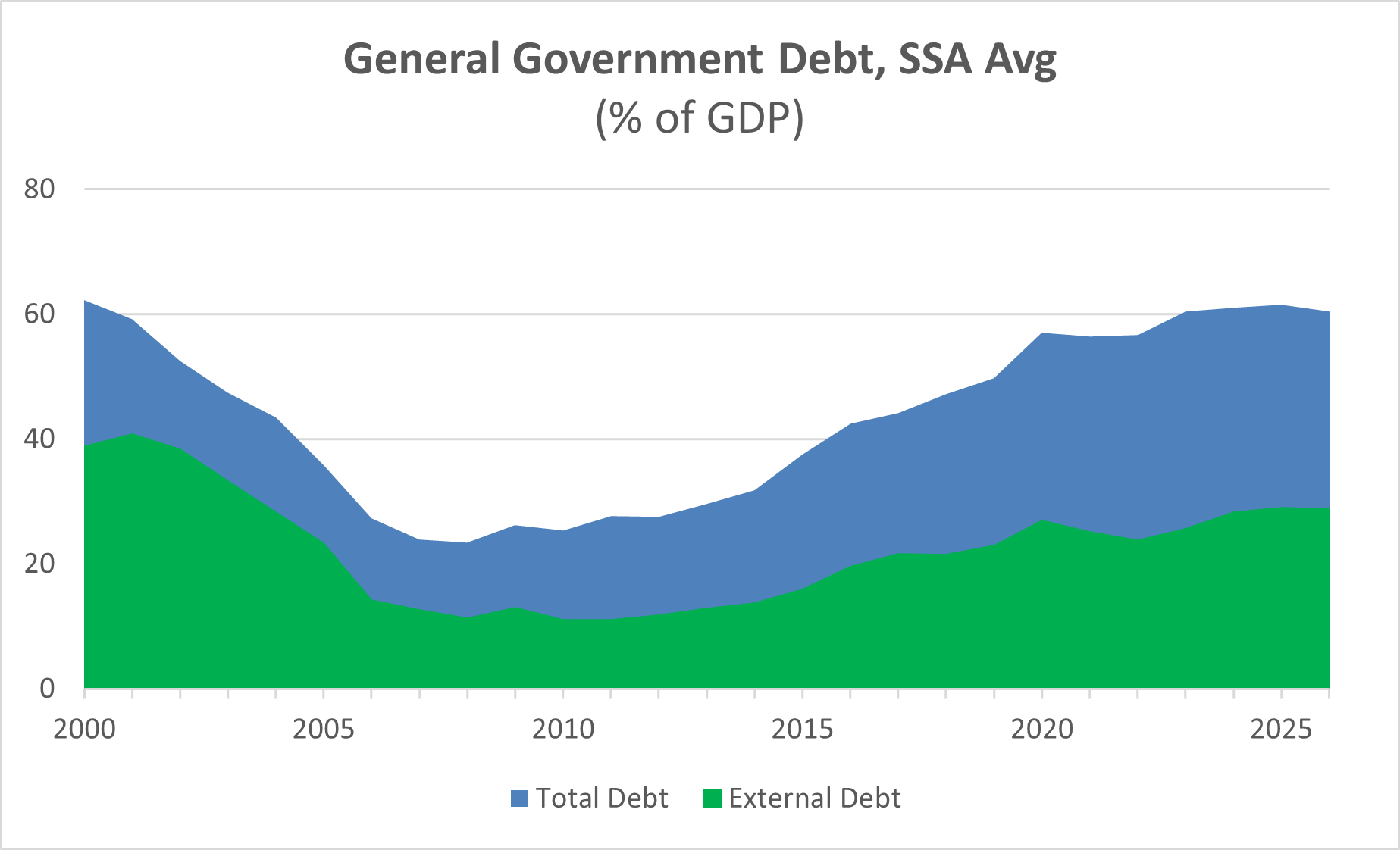

Figure 3. By 2019, SSA debt returned to pre-HIPC/MDRI levels. Source: WB International Debt Statistics

2. Assessing the Common Framework’s First Iteration

Of the 48 DSSI countries, only four (all from SSA) requested debt treatment under the Common Framework, reflecting concerns around the costs and benefits of participation. Uncertainty as to the timeline, the coverage and the magnitude of relief, as well as reputational risks and the desire to avoid default, kept away countries with debt vulnerabilities but not in imminent default risk.

The history of debt treatment initiatives suggests caution in assessing the CF’s ultimate impact. While the CF is a new initiative, it fits squarely within the longer timeline of credit expansion, followed by over-extension, followed by debt relief, and then more credit expansion. This cycle is likely to continue. In its most recent SSA Regional Outlook, the IMF forecasts debt-to-GDP ratios to fall slightly in 2026 (to a median of 53% from 56% in 2025), but also notes ongoing debt vulnerabilities, including high debt-service burdens, stressed domestic debt markets, and uncertainty around the pace of domestic reforms.

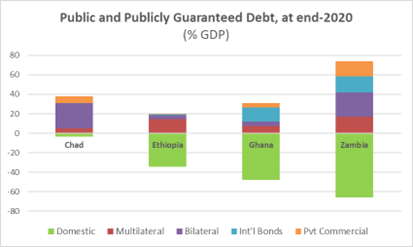

Figure 4. In addition to the return of higher debt levels, the composition of debt reflected the increase in Eurobond issuance and private commercial lending. Source: World Bank External Debt Statistics.

Of the four CF countries, two had already defaulted on Eurobond debt and one defaulted later:

Chad was the first country to request a CF debt treatment, in December 2020, after a fall in oil prices negatively impacted external liquidity. Total government debt was low, but a large portion of Chad’s external debt was held by a single private creditor in the form of an oil-backed loan. Lower oil prices meant Chad’s exports could not fully cover debt servicing obligations. Discussions with the IMF identified a financing gap of USD570 million, but an increase in oil prices had filled the gap by the time the Official Creditor Committee (OCC) formed. The OCC agreed to reconsider future debt treatment if the oil price changed and the signing of the MoU allowed Chad to proceed with a debt restructuring from its main private creditor. The terms are not public, but reports indicate a reprofiling of payments and no reduction in outstanding principal.

Zambia requested the CF in February 2021, but the presence of multiple creditor classes complicated and delayed debt negotiations. In November 2020, the government failed to make Eurobond interest payments, a default event with implications for all of Zambia’s external debt. After extended discussions, Zambia and the IMF reached staff-level agreement on an Extended Credit Facility (ECF) of USD1.3 billion. Subsequently, the OCC reached agreement on a debt treatment involving lowering interest rates and rescheduling maturities through 2043. Zambia reached a deal with Eurobond holders in March 2024, with 90% of holders accepting the deal. However, Zambia has USD3.3 billion in outstanding private commercial debt under negotiation.

Ethiopia requested debt treatment in February 2021, but the Tigray conflict forced a pause in negotiations. Subsequently, Ethiopia ceased making payments on its USD1 billion international bond in December 2023. The government resumed CF negotiations and reached agreement with the IMF on a USD3.4 billion Extended Credit Facility in July 2024 and concluded a deal with the OCC in July 2025, but negotiations with Eurobond holders stalled until quite recently.

Ghana requested debt treatment in December 2022, after government debt reached >80% of GDP, and has used the CF process to accomplish a significant debt restructuring. The government ceased payments on its outstanding Eurobonds in December 2022. The OCC formed when the IMF approved a USD3 billion ECF. The government reached agreement with the OCC on a treatment entailing a comprehensive debt service rescheduling for loans disbursed prior to December 2022, together with a large maturity extension and reduced interest rate. Ghana successfully concluded a debt exchange for its outstanding Eurobonds in October 2024, with investors given the option of either a 37% nominal haircut on a new instrument paying 5-6% interest and maturing in 2029 or a par bond with a 1.5% coupon maturing in 2037.

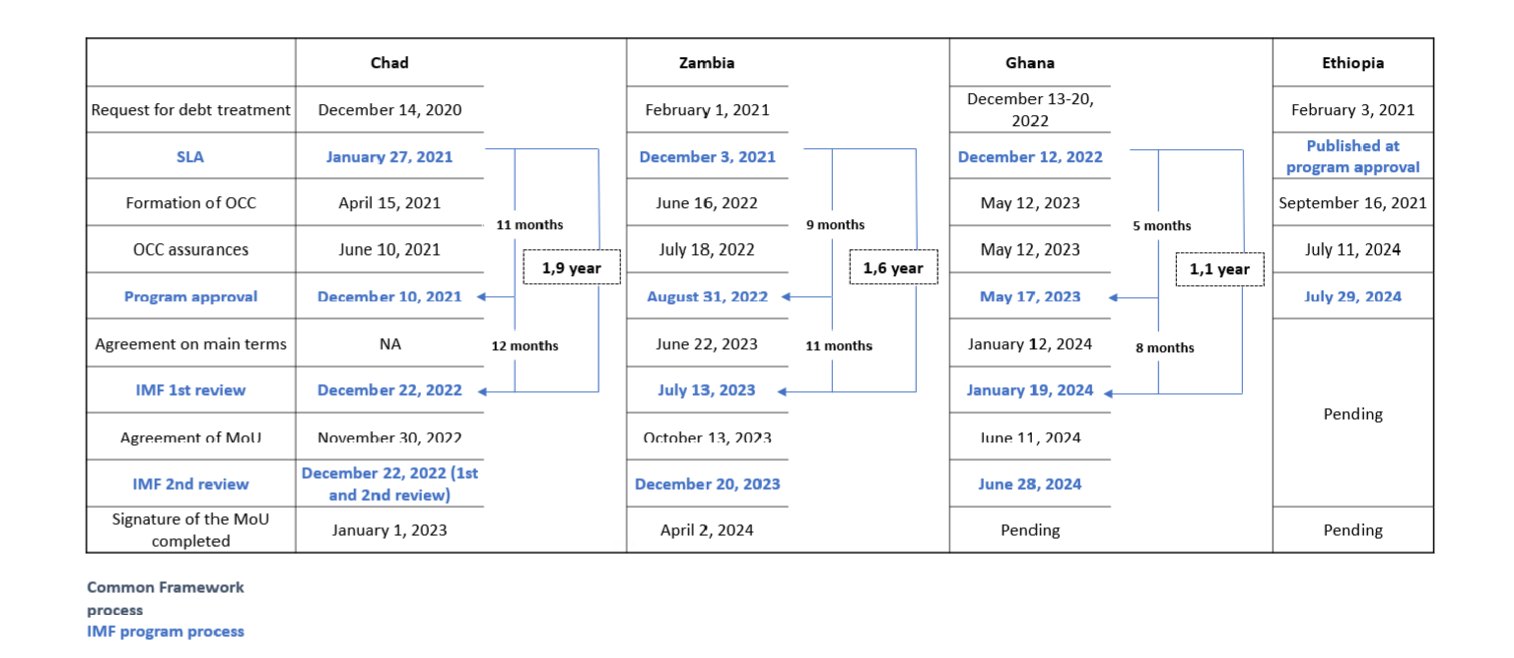

Figure 5. Negotiations dragged during both the pre-restructuring and restructuring stages, but we can observe some improvement in the timelines.

Common Framework debt treatment timelines were generally slower than pre-CF restructurings; however, more complicated debt profiles make direct comparisons difficult (see timeline in Figure 5). Initial uncertainty led to delays in the pre-restructuring steps for Chad and Zambia. Even once MoUs were signed, lack of clarity around comparability of treatment complicated discussions with private creditors. Zambia’s Eurobond settlement came 3.5 years after default, pared down to 2 years for Ghana. Ethiopia recently reached an agreement in principle with bondholders, 2 years after default.

Timelines show no real improvement over median pre-CF times, but the presence of new commercial creditors and deeper domestic debt markets suggest restructuring for Ethiopia, Ghana and Zambia may have been even longer without the CF. While we cannot prove the counterfactual, we can discuss lessons learned.

The G20’s own assessment asserts that debtor countries benefitted from a formal debt treatment process with a single-entry point to official bilateral creditors, but noted the process could be made more timely, predictable, and transparent. In 2024, the G20 International Financial Architecture Working Group (IFAWG) released a note outlining lessons learned and ways forward for improving future debt treatments.[2] The note recommends:

More clarity around the steps of the debt treatment process.

An information sharing mechanism between the IMF-World Bank and the OCC.

Enhanced coordination/information sharing between bilateral and private creditors.

In 2023, the Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable (GSDR) was established to focus on policies and practices around debt sustainability and debt restructuring. The GSDR envisages a debt restructuring architecture that (i) improves information sharing; (ii) clarifies the role of MDBs in provisioning concessional finance and grants; and (iii) clarifies how comparability of treatment will be assessed and enforced.[3]

A complementary G20 workstream addresses how multilateral development banks (MDBs) can more effectively use their balance sheets to increase the availability of financing in developing countries. An independent review of MDB’s Capital Adequacy Frameworks made the following five recommendations:

Adapt approach to risk tolerance beyond rating agency methodologies.

Give more credit to callable capital.

Expand the use of financial innovations.

Work with CRAs to improve assessments of MDB financial strength.

Increase access to MDB data and analysis to shareholders, rating agencies and market participants.[4]

Under South Africa, debt and development played a central role in the G20’s work. The IFAWG pushed forward the ongoing CF work by publishing individual fact sheets on Chad, Ghana and Zambia, and publishing a note outlining a CF process aligned to the GSDR recommendations.[5] South Africa has also overseen the launch of the “One Cost of Capital” initiative to investigate factors making it difficult for low- and middle-income countries to access affordable and predictable capital. However, upon assuming the G20 Presidency, the United States has announced a narrower focus on the “core mission of driving economic growth and prosperity to produce results.”[6]

3. How to view efforts to improve and expand the Common Framework?

The G20 and Paris Club can turn the Common Framework into a regularized and improved process for debt restructurings, but healthy skepticism is appropriate with regard to the rest of the debt agenda. The first iteration of the CF was slow and, in some cases, inconclusive. However, the time from request to Eurobond settlement showed improvement from Zambia to Ghana, and the process can be improved further. Most importantly, this work is already in progress and most of it can be accomplished at the working level, whereas expansion of the CF and the larger debt sustainability agenda would require a level of political cooperation not likely to materialize in the coming year.

The G20 has stated its desire to support countries experiencing temporary liquidity pressures, but expansion of the current debt treatment process faces an inherent conflict between comparability of treatment and the desire to avoid unnecessary defaults. Official creditors can voluntarily restructure debt without triggering a default but involving private creditors in any “voluntary” restructuring would constitute a default. Conversely, allowing private creditors to forego restructuring would violate comparability of treatment. Therefore, the G20 would need to articulate an entirely new process for liquidity management operations separate from the existing CF process.

The larger access to finance and debt sustainability agenda suffers from two key problems that are not likely to be overcome in the short- or medium-term. First, it assumes the key constraint to finance is creditors’ inability to accurately assess risks within LMICs. In reality, the high cost of capital is mostly an accurate reflection of structural risk factors within LMICs. And second, which flows from the first, it assumes the official sector can design a top-down reform program that can fix the problem. This is an especially questionable proposition given the current state of G20 cooperation and the general trend of retrenchment among developed world governments.

The key takeaway is that cycles of over-extension and debt forgiveness belie the structural constraints of LMICs in general and SSA in particular. The G20 and other institutions can best help to expand access to affordable financing by focusing on concrete steps to address the existing structural constraints and help improve the capacity of LMICs to manage public finances, public investment and public debt.

Further, while the United States will not aggressively push the debt sustainability agenda, the U.S. government has signaled a desire to improve debt transparency, address the treatment of bilateral creditors in debt negotiations, and see the World Bank and IMF return focus on their “core missions.”[7]

So, what can the G20 do?

First, the G20 should formalize a Common Framework process that includes earlier private sector involvement and better information sharing. While the CF is an official sector-led initiative, it relies on the involvement of private sector creditors, which are likely to only play a bigger role going forward.

Second, it should accept that debt vulnerabilities are largely a reflection of structural factors and commit to work that impacts those factors. LMICs, especially in SSA, are institutionally younger, compose a smaller share of the global economy, and have notable governance weaknesses. These are the key drivers of sovereign risk premium.

Finally, it can continue taking steps to help MDB more efficiently deploy capital. Bilateral aid flows are likely to get smaller, making MDB balance sheets even more important. Efforts to expand lending operations while maintaining MDB credit worthiness can make more liquidity available to LMICs, and innovative financing efforts can crowd-in private financing.

Suggested Areas of Work for the G20

Below is a list of actions the G20 could take, both in the short term and in the medium- to long-term, organized into the three categories mentioned above:

Formalize the Common Framework process:

Articulate a clear Common Framework architecture. The case-by-case approach is warranted, but the introduction of benchmark timelines, information sharing protocols, and comparability of treatment methodology would help investors to clarify resolution and recovery risks.

Formalize the role of private investors. Enshrining a debtor-led committee of all creditors and/or a separate Private Creditor Committee would formally involve private creditors early in the CF process and create a process for sharing information on the creditor’s debt sustainability discussions and potential debt treatments.

Clarify the role of state-affiliated private creditors. Some investors have traits of both official bilateral and private commercial creditors. As this type of lending is likely to increase going forward, the G20 and Paris Club should work towards clear criteria for its treatment.

Acknowledging and addressing structural constraints:

Adopt a domestic debt workstream. One that promulgates principles for domestic debt market development in LMICSs; a standard disclosure template for domestic debt data; and a toolkit to guide sovereigns through bouts of domestic debt distress with minimal damage to the baking sector.

Create a centralized forum in which LMIC governments can seek support and technical assistance for capacity development at the national level. The long-term goals of development and debt sustainability will require increased national capacity in the areas of public financial management, debt management, and public investment management.

Help to improve investor relations capacity among creditor governments. In addition to better overall debt management practices, sovereigns would benefit from improvements in how they share relevant information and communicate with investors.

Support for Multilateral Development Banks

Continue work on MDB Capital Adequacy Frameworks. Given the declining appetite for assistance among donor countries, MDB balance sheets, along with their expertise and risk management capabilities, will become more important.

Establish a framework for liquidity management operations. Liquidity instruments already exist. However, the G20 could explicitly highlight instruments and facilities best suited to address specific debt vulnerabilities and incorporate them into a framework for addressing liquidity concerns without triggering default.

Support innovative finance for development. LMIC governments are constrained by short-term current expenditure needs, long-term development needs, and insufficient domestic revenue. Instruments like credit guarantees, insurance, and callable liquidity facilities can help to alleviate budget pressure and create new investment opportunities for private sector investors.

[2] G20. 2025. G20 Note: Steps of a debt restructuring under the Common Framework. G20 South Africa 2025.

[3] The G20 is an intergovernmental forum comprised of 19 nations plus the European Union (EU) and the African Union (AU). The Paris Club is a group of major creditor countries aiming to provide a way to tackle debt problems in creditor countries.

[4] Eligibility is open to all IDA countries and countries defined as least developed by the United Nations that are current on any debt service to the IMF and World Bank

[5] G20. 2025. G20 Note: Steps of a debt restructuring under the Common Framework. G20 South Africa 2025.

[6] U.S. Department of State. “Unites States Assumes Presidency of the Group of 20”. Dec 2025. Accessed here: https://www.state.gov/releases/office-of-the-spokesperson/2025/12/united-states-assumes-presidency-of-the-group-of-20/

[7] U.S. Department of State. “Unites States Assumes Presidency of the Group of 20”. Dec 2025. Accessed here: https://www.state.gov/releases/office-of-the-spokesperson/2025/12/united-states-assumes-presidency-of-the-group-of-20/